DIBS for Kids: Building Great Reading Experiences for Every Child

DIBS for Kids believes that every child should have a great book, waiting for them at home. And the easiest way to get books to kids is through their teachers. So DIBS for Kids is bringing books into the schools and have set up and ingenious system to make it all work so kids can take books home from school. The program is a concrete effort to get kids reading, which is critical. As such, we were delighted to give this literacy nonprofit, a helping hand with a small grant. We spoke to Founder and Executive Director David Orrick, to learn more about this work:

Kars4Kids: How does your program differ from the local library?

David Orrick: While local libraries excel at providing a wealth of books that students can freely check out, DIBS encourages communities to also move the distribution of take-home books directly into the classroom. By doing so, DIBS helps communities ensure every student has a book, every school night – even on the days when a trip to the school library might not be feasible. We also differ in that our books are leveled for students. This means that when they pick a book from the DIBS Classroom Library, they are picking a book that they can independently read at home, without instruction or assistance from an adult or older sibling.

Still, we don’t see our end-goals as competing with libraries. Instead, DIBS’ major focus is to build great reading experiences in the K-3rd grade years that make our students want to go to the library as they continue their academic and life paths. We like to say we’re helping libraries grow and expand their future customer base.

Kars4Kids: What role do Americorps volunteers play at DIBS for Kids?

David Orrick: DIBS for Kids is in our 5th year of an AmeriCorps VISTA grant that has brought 20 full-time volunteers to our organization since 2015. This grant was our most critical initial step toward establishing DIBS as an organization – allowing us to have between two and seven full-time central office roles before we had the funding that would allow for such staff. They have helped us with everything from program refinement, to grant writing and marketing. The idea behind VISTA is to build organizations’ capacity to function long-term without the need for VISTAs, which has proven to be exactly what we’ve experienced. Our VISTAs have helped us expand from serving 450 students in 2015 to serving 3,000 in 2019, and have positioned DIBS to not require VISTA after this 5th and final year of our grant.

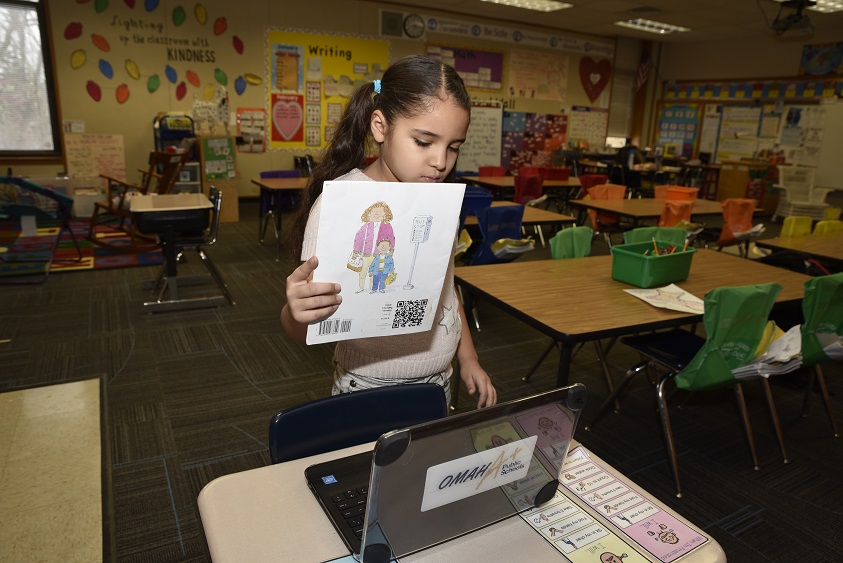

Kars4Kids: How difficult is it for kids to learn how to scan the barcodes and return the books?

David Orrick: Learning our technology is quite easy for our students, but varies significantly by age group. In a 2nd or 3rd grade classroom it takes most students one or two days to learn how to operate DIBS and is extremely quick and easy for a teacher to implement. In a kindergarten classroom, on the other hand, we like to tell teachers to plan for 1-2 weeks of training where they (or a volunteer) are hanging out by the DIBS computers showing students the routine. Fortunately, Kindergarten teachers are often the very people with the uncanny patience needed to spend that extra time with students early on.

Still, we like to communicate this up front before a teacher decides to adopt DIBS to make sure they are ready for their classroom “launch” of the program. Probably the best part of starting the students in Kindergarten, though, if a teacher does opt-in to the program, is that then their students don’t know any different in future school years – they just think every student across every school is taking books home every night using a cool technology. So much so that if you find a student that had the DIBS program in Kindergarten and try to train them on DIBS when they enter 1st grade, they will shoo you away and say “I got this, I don’t need help” – one of our favorite things to hear as we start each school year.

Kars4Kids: Why is the physical reality of an actual book with pages, still important for kids? Isn’t the vast amount of text they can access online, enough?

David Orrick: We’ll be the first to say that it is very ironic that we’re a “technology-based nonprofit” that is advocating for the resurgence of physical children’s books. For the record, we are 100% in favor of students reading books wherever they find them most accessible: on an eReader, on a website that offers age-appropriate books, or in physical form. I designed DIBS initially based on my experience teaching in two very high-poverty schools where those first two options simply weren’t in play: if you didn’t put a physical book into your students’ hands on a school day, they had no access to reading opportunities that night.

Over time, we’ve come to believe this isn’t just a poverty issue. With all the technology in homes these days, and with all the difficulty teachers have finding good “homework” opportunities for students, we deeply believe that supporting fun, daily in-home routines between child and parent – or child-and-cat as some of our students prefer – is a huge support for our teachers and is as noble of a cause for our students in the 21st century as it was in the 20th.

Kars4Kids: Can we prove the link between having access to books and academic success?

David Orrick: Scholastic is a partner of ours who has gone to length studying this topic (http://teacher.scholastic.com/products/face/pdf/research-compendium/access-to-books.pdf) as has the national Campaign for Grade Level Reading (https://gradelevelreading.net/). In both cases, the evidence seems very clear that access to books is a critical step toward students achieving 3rd grade reading proficiency, but neither is specific to DIBS. From my own experience in the classroom, it’s obvious that how something is implemented can make-or-break if it’s actually affecting students’ lives. For this reason, we are embarking on an external evaluation of DIBS in the 2020-2021 school year that will attempt to isolate DIBS at scale against a control group and help determine if our implementation of the program across our schools is high-quality enough that it’s actually affecting students’ literacy outcomes.

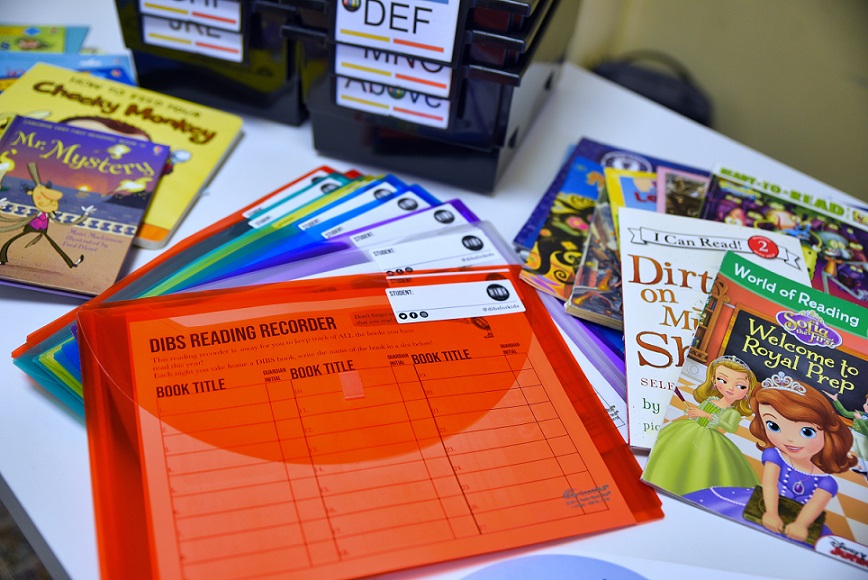

Kars4Kids: Who chooses the books? On what basis are they chosen?

David Orrick: Our School Support Director, Marie Kovar, comes to DIBS as a former Bi-Lingual School Psychologist with extensive experience with students and in schools. In the last 12 months, she has worked closely with our publishing partners to revamp our approach to determining which books students might like to read and to ensure we have systems in place to ensure any books deemed inappropriate for DIBS are removed from future orders. Probably our biggest initiative has been trying to adjust DIBS’ catalogue within schools that have high English as a Second Language (ESL) populations to ensure students are also able to access books in their native language when possible.

Additionally, we choose diverse books. The reason for this is two-fold: 1) So that all students feel represented in what they are reading and so that they can see themselves in literature. 2) So that all students can read about people who are different from themselves, learn about others and gain a better understanding of the world around them.

Finally, we choose books that are high-interest, fun and based upon guided reading levels, so that on any given night a student can independently read their book or read it to their family without instruction.

Kars4Kids: Do you have any advice for parents on how to choose books for their children? How do you choose something your children will actually want to read?

David Orrick: This is difficult since parents have so many diverse backgrounds and experiences when it comes to books. At DIBS, we put a premium on two things: 1) Trying to find books that are appropriately leveled for students to help them read independently even on a night where they might not have a parent or guardian to read with, and 2) Trying to ensure students also have opportunities to read off-level – to pick up a book simply because it’s a fun book to read. We help teachers accomplish this through a program called “Free Choice Friday” which allows students to select books from any DIBS bin on Fridays and for the weekend.

We also encourage teachers to open up their DIBS books for in-class reading and to monitor students’ reading levels to see when they are ready for increasingly difficult books. We do not think this approach is for every teacher, nor for every parent, but it has been a helpful framework for us to try to learn how you might scale something that brings unique value to the parents and teachers we serve – something they otherwise likely can’t do without support.

Kars4Kids: Do you have any plans to take your organization national?

David Orrick: DIBS is poised for regional and national expansion and is already piloting our model in communities outside of Omaha, but our #1 focus is to first demonstrate the extent that a community like Omaha can actually make measurable literacy gains by implementing the program at scale. For this reason, we’re hyper-focused on growing to serve all 46 local elementary schools that have a 70%+ poverty rate before we’re exploring large-scale partnerships with schools and districts outside Omaha. Though I’ll also say that it has historically been nearly impossible for us to turn down principals and teachers who want DIBS in their classroom, so we’d strongly encourage schools to reach out to us. We can often find a way to make the program happen regardless of your location.

Kars4Kids: What is next for DIBS for Kids?

David Orrick: In the summer/fall of 2021 we will have evidence-based results showing if and to what extent DIBS is actually impacting literacy proficiency in our schools. If it is, we believe we would be on a 5-year plan to make DIBS a district-wide initiative here in Omaha, and a 10-year plan to make it available to all districts nationwide. If it is not impacting literacy proficiency, we will likely “pivot” the program and still offer it to schools that want a better book distribution system, but with less emphasis on district-wide implementation.