Page Ahead Children’s Literacy Program: Books to Have and to Hold

Page Ahead Children’s Literacy Program is doing something novel, so to speak, to further literacy in underserved Seattle neighborhoods. They have created little “book nooks” for children where they can discover the joy of holding a book; look at the pictures; and if all goes well, eventually read the book to completion. It’s one new way to get books into the hands of those who need them the most.

Our small grant program allows us to lend support to initiatives that fit in well with our own mission. We see literacy as the crucial first step to academic success and a brighter future. Page Ahead is doing something really different and we could easily see how their program could lead to lifelong lovers of books. We put some questions to Page Ahead Children’s Literacy Program Development Manager Rebecca Brinbury to find out how the magic happens:

Kars4Kids: Can you tell us something about your demographic? Who are the children you serve at Page Ahead?

Rebecca Brinbury: We focus on kids’ early reading journeys, with particular emphasis on preschool and kindergarten through second grade, because stopping reading gaps before they start is a really powerful intervention. And we’re doing this work with an eye toward educational justice and more equitable distribution of resources, so we focus on kids in majority low-income communities, who, thanks to entrenched racism and structural barriers, also tend to be from families of color and/or Hispanic/Latinx families. Basically, our community works to get books to kids who could benefit from them most.

Kars4Kids: The Page Ahead website says there are 22,000 children in Seattle who live in book deserts. For the sake of our readers, can you define “book desert” and why such a phenomenon exists? Which leads to the obvious question: can’t children just go to the library if they don’t have books at home?

Rebecca Brinbury: We’re all familiar with the idea of a “food desert,” an area where fresh food isn’t easily obtainable. Book deserts are similar, but for reading material—book deserts are areas where reading materials are hard to get ahold of. The organization Unite for Literacy maintains a map of book deserts that is fascinating to explore, where you can see census data on how many homes have at least 100 books in them. If you look at Seattle on that map, the book deserts are where you’d expect them to be—while the wealthier enclaves have lots of books, those with lower incomes don’t.

The book desert phenomenon exists for the same reason any other resource inequality exists; books cost money; money is inequitably distributed; and many families have to prioritize food, shelter, clothing, and other necessities. Yes, libraries provide crucial services, but they cannot stand in for having books at home.

For example, school and classroom libraries are a big part of a child’s reading journey at school, but I know at my daughter’s school, the younger grades aren’t allowed to bring their school library books home—these have to stay in the classroom. And public libraries are fantastic—maybe my favorite places in the world!—but when you’re seven and you live a mile from your neighborhood library, you need your grownup to go with you, and if that grownup’s work hours don’t line up with the libraries open hours, you’re out of luck.

But say you are able to go to the public library and check out your Pete the Cat books. Hooray! In Seattle, those will be due back in three weeks. And there is a joyful novelty in getting to experience a new story, which is so important. But being able to read and reread the same material is a foundational part of reading fluency, too. So owning your own books, and reading them over and over again, is really important in building your literacy skills.

On Equity in Education

Kars4Kids: Your website talks about the need for equity in education and opportunities. Why are resources distributed in an uneven manner in the public schools? Who is responsible for this situation and how is Page Ahead helping to narrow the gap? Are you working with the parents, too?

Rebecca Brinbury: Ah, if we had an easy answer to this question, Page Ahead could cease operations tomorrow! Unfortunately that is not the case. Smarter people than me have done plenty of research on inequity in public education, but it basically comes down to entrenched inequitable school funding models, which reflect and perpetuate the larger inequitable resource distribution among people and families in our society, particularly along racial lines. In Seattle, for example, the median net worth for Black households is only 5 percent that of white households. And since school funding tends to be tied to local property values, inequitable and racist housing models and gaps in median income and generational wealth make themselves known at the school level too. Plus, in Washington, the state struggles to pay for basic education costs, even though it is constitutionally required to do so, so districts rely on passing levies, which is much harder for districts in poorer areas to do because their voters are less likely to approve “extra” costs.

So the problem is multifaceted and generations in the making and is a legacy of a white supremacist system that has historically centered (if even unconsciously) the needs of white kids in general education. And Page Ahead can’t fix that.

But! There is a ton of research that shows that when you have access to books in the home in childhood, regardless of your parents’ education or income level, you are more likely to succeed in school and in life. Academic success tends to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty. So that’s our focus—equitable book access for ALL kids.

We are a small team (just four employees, plus a couple hundred AWESOME volunteers), so our model is very decentralized. We work directly with schools and organizations to help them get books in the hands of the kids they serve; that means our immediate partners are school librarians, teachers, early childhood educators, and more. We also support family reading time with family literacy nights and prompts for questions to ask during shared reading times.

Free Library “Oases”

Kars4Kids: Talk to us about the Book Oasis project. Can you describe these “oases” for us, please? How did Page Ahead come up with this fantastic idea?

Rebecca Brinbury: Our Book Oasis project installs, maintains, and refills Little Free Libraries in Seattle-area neighborhoods with the most limited access to books. Originally conceived of as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and how much harder it was for kids to find new books to read with school and public libraries closed, each Book Oasis provides a constantly refilled pipelines of brand-new, high-interest title for babies through young adults from our book stock.

Custom designed for little browsers (including shelves closer to the ground that face book covers out), each Book Oasis is maintained and refilled by Page Ahead volunteers. Located near Seattle schools we already serve with our other programs, Book Oases further expand these students’ access to books, strengthening home libraries and increasing community book circulation.

The first Book Oases were installed in the High Point community in West Seattle in March 2021; we’ve now installed eighteen total Oases in more than a dozen neighborhoods. Thanks in large part to Page Ahead’s amazing corps of Book Oasis restock volunteers, our Oases are now putting an average of more than 140 books a week out into the community!

Combatting Summer Learning Loss

Kars4Kids: How is Page Ahead combatting summer learning loss?

Rebecca Brinbury: I think the first question to ask is why we are combatting summer learning loss. And that’s because it’s where the majority, about 80%, of the “achievement” gap comes from—that is, the gap in testing scores between kids in families experiencing low income and their better-off peers. Even though those kids learn at the same rate during the school year, when the educational “faucet” is turned off, the kids whose families have more resources are better able to keep learning during the summer outside of school, but the others aren’t. So if you can keep kids from sliding back during the summer, you can keep them on even footing all year round, and the “achievement” gap doesn’t get established in the same way.

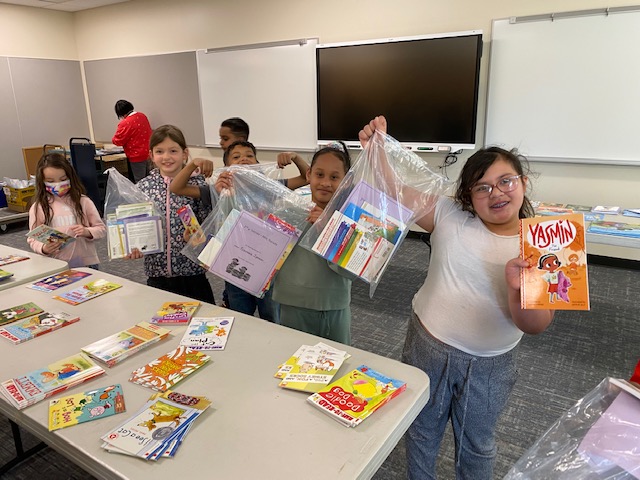

And we do that through Book Up Summer. Based on a highly regarded 2010 Department of Education-funded study, Book Up Summer gives students in grades K–2 reading material for summer vacation. In late spring, students choose 12 new books from a special book fair at their school. Prior to the book fair, students and their families are invited to a literacy night where they learn about the program and discuss book selections.

Instead of a summer setback, Book Up Summer students experience a boost! According to 2018 Seattle Public Schools test data, Book Up Summer students show an average improvement in reading skills of 2.63 points over the summer for rising first graders and 1.84 points over the summer for rising second graders. To see these students, who would typically slide back, actually gaining reading skill is a powerful endorsement of this summer reading model.

Access to books through Book Up Summer has also functioned as a protective factor during the pandemic, which has knocked students back at all levels. Seattle low-income fourth graders who had participated in Book Up Summer in their K–2 years have slid back nearly four points less in their reading scores than their statewide low-income peers (a drop of 9.7 points for Seattle Book Up Summer students vs. 13.3 points for statewide low-income students).

Since we first piloted Book Up Summer a decade ago, we’ve put nearly 1.4 million self-selected books on kids’ shelves in more than 100 schools statewide.

Pushing Against the Achievement Gap

Kars4Kids: What makes a child “kindergarten ready” and how are you helping to move the children of your community closer to that goal?

Rebecca Brinbury: “Kindergarten readiness” is a measure of how prepared kids are for elementary school. But it isn’t about how many letters or numbers they know. It’s more about how ready they are to learn, and includes everything from motor skills to social-emotional development to persistence capacity and more. One crucial part of that is language and preliteracy skills, which is where our Story Leaders program comes in.

Story Leaders is a reading intervention that trains educators and families in evidence-based shared reading techniques for preschool children (that is, reading stories together, asking questions about the books, and so on). Story Leaders is designed to rapidly develop vocabulary and language skills and provides eight free books that the students have read in class during the school year to take home, building both their home libraries and reinforcing the home–school connection.

Pre-literacy skills like print awareness, self-regulation (the ability to sit still and listen to a story), and exposure to a high number of words are the foundation of later reading success, and shared reading like what we teach through Story Leaders is a proven way to support the development of those skills. And because Story Leaders is offered at government-supported preschool programs that serve families experiencing poverty, we’re giving those kids a leg up on their reading skills before they even get to elementary school, as a preemptive pushback against the aforementioned “achievement” gap that they are statistically likely to encounter.

Are Books Still Relevant?

Kars4Kids: Why is it important to build “joyful” reading habits? Where does technology fit in with all this? Are books still relevant? You offer three programs that specifically address this critical need. Can you tell us a little bit about them?

Rebecca Brinbury: Obviously I am very biased, but yes, books are SO relevant! As any publishing professional will tell you, a “book” is a way for a story to get across, regardless of whether you’re reading it on a page, on a screen, or through an audiobook. And personally, I love my ereader for requesting and checking out ebooks from the library, for example. But “traditional” printed books are still very much central to the learning and literacy process—especially because it is much easier to distribute books than it is to distribute digital devices. Plus, even if they have access to them, kids don’t usually own their digital devices—they belong to the school district, or to an adult in their household, or so on. Kids can own books, and ownership is powerful. (Plus books don’t need to charge, and when they break, they can be fixed with a little tape instead of a support ticket and a Master’s degree!)

We help make those joyful reading connections with books through our Story Time program, in which trained volunteers visit preschool and kindergarten classes to read books, sing songs, and do crafts on themes like “friendship” or “springtime”; we also work with partner schools and volunteer groups to hold one-off reading events, during which kids pick a book to read with visiting volunteers and then they get to take it home and keep it. And in a throwback to the original name Page Ahead was created under—Books for Kids—Page Ahead works with fellow nonprofits and schools to provide books that they can give the kids they serve.

Kars4Kids: Talk to us about your volunteer program. How do you manage such a large team? What kind of role do they play at Page Ahead?

Rebecca Brinbury: My amazing colleague Stacey Lane runs our volunteer program, along with the fantastic Lisa Ceniceros, our literacy programs manager. They train and support our program volunteers, like those who do Story Times or restock Book Oasis. Stacey especially does a ton of work with our corporate volunteer groups, who tend to do project-based volunteering, such as decorating bookmarks or preparing bunches of bookplate stickers.

Last year, we had 187 volunteers who donated 2,332 hours total (pre-COVID, we had closer to 400 and 500 volunteers annually, but of course the volunteer opportunities were more limited last year). The value of a volunteer hour in Washington in 2021 was $34.87; that means Page Ahead volunteers donated the equivalent of $81,316.84! We truly could not get this work done without them. And anyone who is interested in learning more about volunteering can go to pageahead.org/volunteer to learn more!

Measuring Success

Kars4Kids: Do you have a way to measure the extent of your impact and success?

Rebecca Brinbury: We track our numbers internally, of course, about the number of books distributed, kids served, and so on. And we also get testing data from the schools we work with in Book Up Summer to help track reading scores (though of course COVID interruptions to standardized testing has interrupted that for the last couple years).

We also survey our educators and families about the impacts of our programs. 98 percent of teachers responding to our survey in spring 2022 agreed that Book Up Summer helps to build a culture of reading for their students’ families; 99 percent agreed that it makes a positive impact on their students’ attitudes toward reading and fosters engagement with reading; and 100 percent agreed it increases their students’ access to books in the home.

Also in spring 2022, 69 percent of families responded that Book Up Summer would increase their future family time spent reading together; they also reported that their children’s home libraries grew by an average of 62 percent thanks to Book Up Summer.

Kars4Kids: What’s next for Page Ahead?

Rebecca Brinbury: Growth! Book Up Summer is expanding to new schools in Spokane, the Yakima Valley, and Pierce County. Story Leaders is adding a bunch of kiddos in the Highline district. And that’s just for this school year!

As they work to make up for pandemic disruptions to their learning, more kids need more books than ever. So we’re working hard to raise the money and build the systems we need to make sure those kids have plenty of books on their shelves. We’re grateful to Kars4Kids for joining us in this work and invite everyone else to find out how you can be a part of our partnership too at pageahead.org/get-involved.